The Long Tomorrow — The New Inheritance Gap & The Rise of Intergenerational Gridlock (7)

The Clock Is Slipping & No One Is Rewinding It

The Long Tomorrow explores how AI, robotics, and longevity science improvements are reshaping society and the second half of life.

If you're curious where the future's headed — click the “subscribe now” button just below and become a Paid Subscriber to gain access to the full channel.

Mainline articles on The Long Tomorrow like this one remain free to all though 12/31/2025.

Living longer doesn’t just delay death—it delays everything that used to follow it. Inheritances, leadership transitions, and generational mobility are all being pushed back—and it’s starting to show.

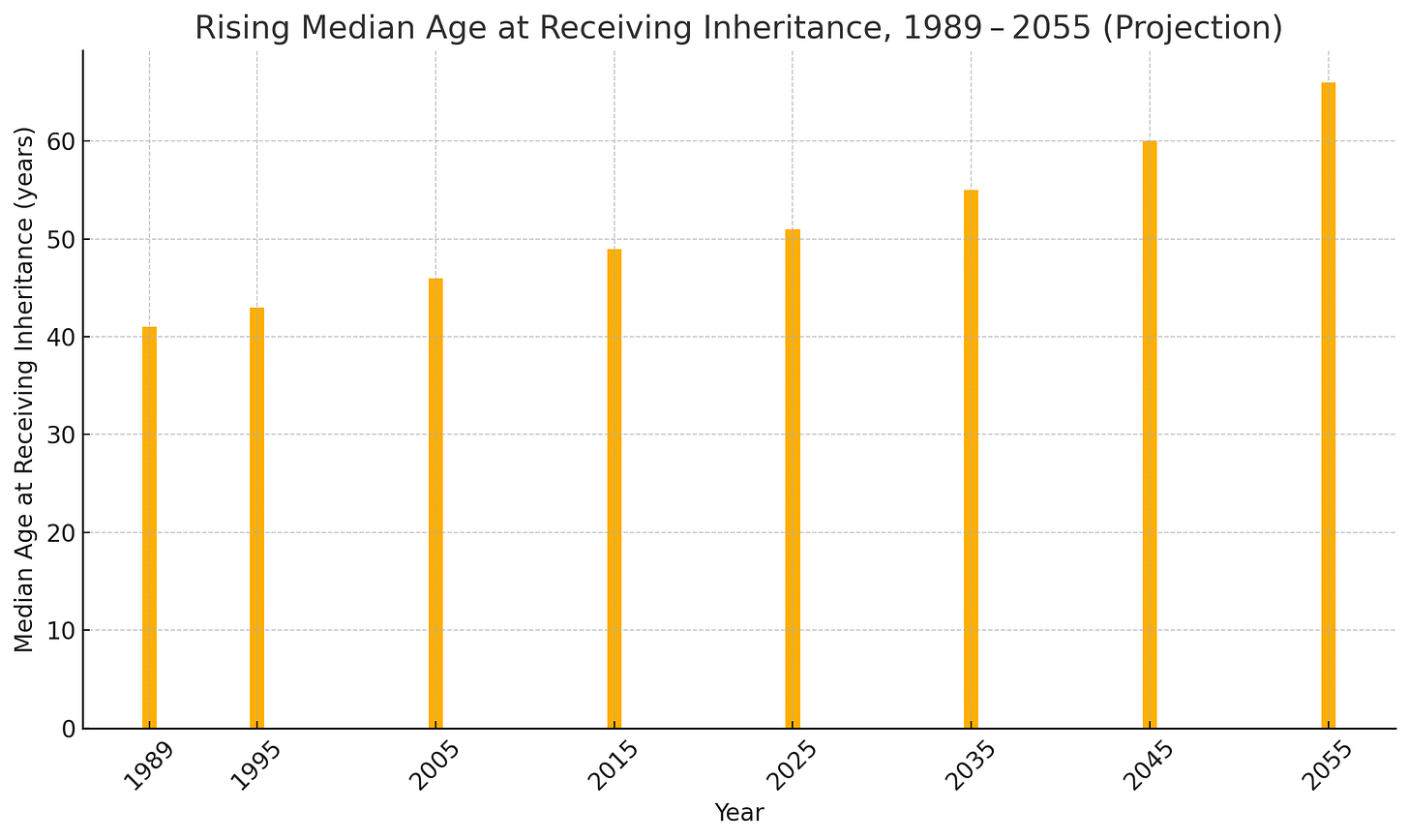

Every few years the headlines trumpet “the greatest wealth transfer in history,” and the numbers duly climb: Cerulli now pegs the hand-off at $124 trillion between 2025 and 2048—a figure that has already drifted upward twice since early 2024 Cerulli Associates. Yet the raw total obscures a more consequential shift: the timetable of inheritance is elongating even faster than the balance sheets are swelling. SeniorLiving.org, parsing Federal Reserve and actuarial datasets, finds that the average American heir—across all asset tiers—once took possession at age forty-one (1989), but today does so closer to fifty-one; the Los Angeles Times corroborates with a similar decade-long slip in receipt age, observing that more than a quarter of bequests now arrive when the beneficiary is already sixty-one or older. The bar chart below projects that trend through 2055, pushing the median hand-off into the mid-sixties unless something dramatically alters the pipeline.

For now nothing suggests acceleration—indeed, everything about modern longevity and late-career economics suggests additional drag. At the ninetieth percentile of income the actuarial midpoint already peeks into the low-nineties for men and women, and essays collected by the Society of Actuaries this spring argue that AI-driven diagnostics, regenerative therapies, and organ-on-chip drug testing could conservatively tack another five to seven years onto healthy lifespan over the next two decades—gains that will disproportionately accrue to exactly the households with the largest estates to pass downstream dr.soa.org. Longer lives, richer end-of-life portfolios, slower hand-offs: the flywheel of inter-generational mobility no longer coasts; it grinds.

When the Inheritance Becomes a Retirement Top-Up, Not a Launchpad

Because the money arrives later, it behaves differently. Forty-something heirs used to roll an inheritance into business formation, or a move-up home; fifty-something heirs are more likely to splash it against a mortgage pay-down, looming college bills for their own kids, or catch-up contributions to tax-deferred accounts they suspect will still fall short once required minimum distributions (RMDs) finally kick in at seventy-three and—under current SECURE 2.0 law—seventy-five for those born 1960 or later. SmartAsset. Draft proposals floating on Capitol Hill would nudge the RMD start toward seventy-six, but every forward nudge on distribution age doubles as an incentive for the donor generation to keep assets sheltered (and voting) until the tax code pries them loose.

Meanwhile, the median first-time U.S. home-buyer is thirty-eight, a full decade above the 1980s baseline. National Association of REALTORS® Thirty-year mortgage borrowing costs linger between 6.74% and 6.95% so far this year, starter inventory is strangled by Baby-Boom owners who can age-in-place with Medicare home-health supplements, and younger buyers stare at a down-payment horizon that lengthens each time asset inflation outpaces wage gains. That capital bottleneck is no longer anecdotal; it is structural, replicated across metros from Tampa to Tacoma, and it directly traces to cash that sits in brokerage accounts of septuagenarians (or older) who quite rationally hesitate to liquidate appreciated stock positions that would trigger hefty embedded gains if sold while alive.

Friction in the Real Economy: Capital, Careers, and Homes Come Late

The OECD’s Employment Outlook 2025 is uncharacteristically blunt: job-to-job mobility—an essential lubricant for wage growth—declines steeply in jurisdictions where a high share of workers aged sixty to sixty-four hold on to senior roles. The United States, already an outlier for employer-sponsored health coverage tied to tenure, displays the pattern most starkly: outside the tech sector, voluntary quits plateau at thirty-five and fall off a cliff after forty. Wage growth follows.

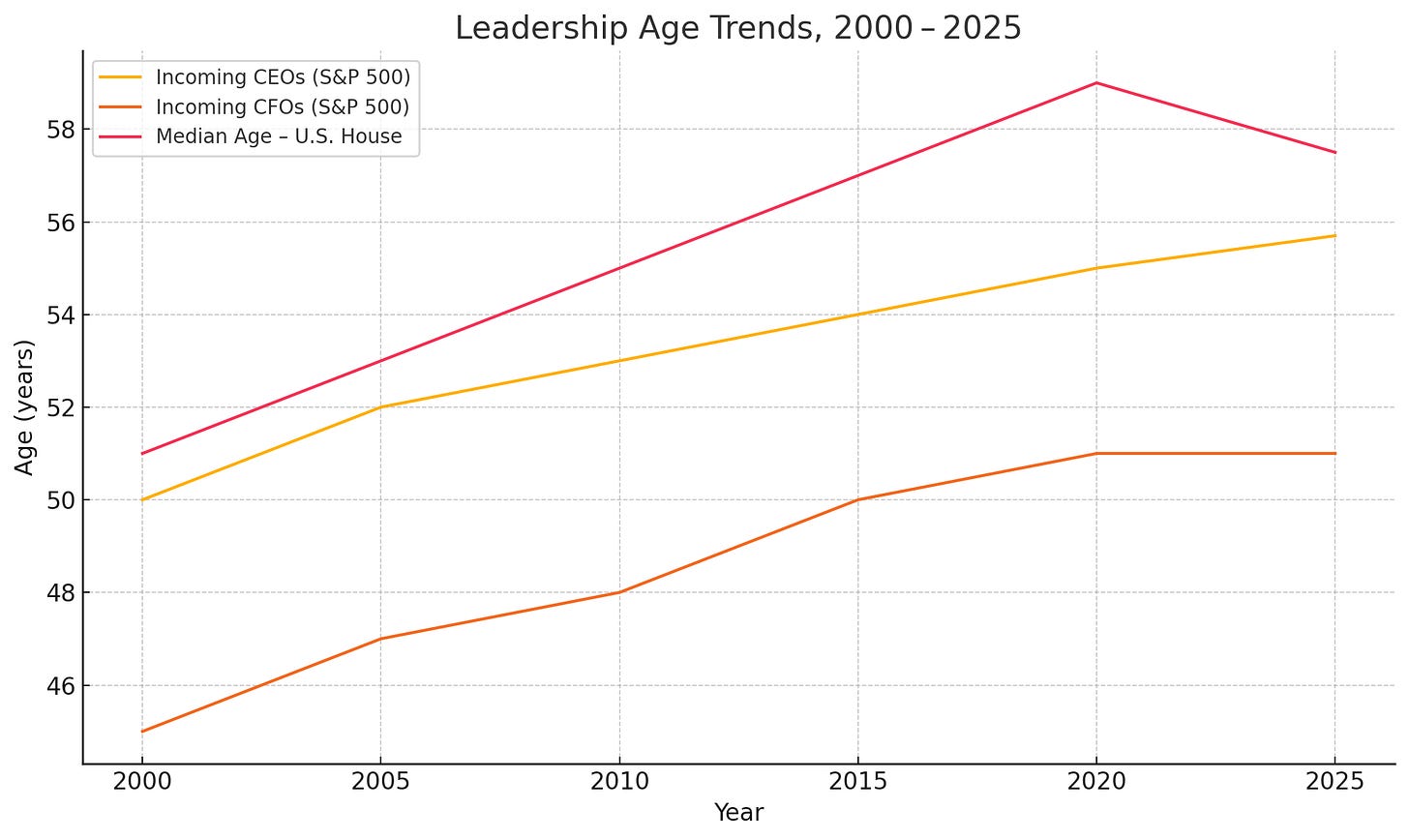

Corporate leadership data echo the stalemate. Spencer Stuart’s 2024 census of CEO transitions puts the average incoming CEO at 55.7, with nearly one in six aged sixty or older. Incoming CFOs hover around fifty-one, and House members in the 119th Congress settle at a median 57.5 years. Pew Research Center The timeline chart below shows all three lines ratcheting upward through 2000-2025 with only minor dips in recession years, underscoring how longevity gains compound institutional inertia.

Add housing and you create a feedback loop: older leaders hold high-salary positions, accumulate more real estate, and defer downsizing; younger workers face stagnant wages, thin inventory, and record prices. No wonder the Kauffman Index reports that the share of first-time founders under forty has fallen fifteen percent since 2010, despite venture capital being flush with liquidity. Capital exists, but it sits behind glass—acquirable only at exit events orchestrated by boardrooms populated with peers of the original holders.

The Family That Waits: 2025 → 2055

Within households, the strain expresses itself less in spreadsheets than in psychology. Gen X heirs in their late fifties begin caring for parents in their eighties while subsidizing children in their twenties—and soon enough grandchildren—without relinquishing the hope that an eventual bequest will cushion a retirement whose investment horizon now reads 2050-2060 rather than 2040-2050. Meanwhile, demographic projections indicate that the wealthy half of the Millennial cohort may see median life expectancy push past one hundred by 2055, especially if AI-accelerated drug discovery and in vivo gene editing deliver on even half their clinical trial pipelines. That means some Millennials will receive an inheritance, manage it for thirty years, and still pass it on at age eighty-five or ninety to heirs already midway through their own careers. The chain of capital allocation lengthens; its kinetic energy weakens.

The emotional consequence is a modernized Prince-Charles syndrome: heirs school themselves for roles that materialize decades late, if at all. Psychologists at the 2025 APA symposium flagged “identity foreclosure” among upper-middle-class forty-somethings who postpone entrepreneurial risk until after the inheritance, only to find that by fifty-five they no longer possess the appetite—or the market finds younger competitors more fundable. Such frustration curdles into quiet resentment inside families, crystallizes into populist rhetoric outside them, and primes the polity for redistributive experiments that treat private dynasties as public problems.

Breaking the Bottleneck: Tactics That Work (for Now)

Warm-hand giving—annual-exclusion gifts, 529 super-funding, qualified charitable distributions—operates on the edges but grows in importance as both donor and donee tax brackets spike if the 2025 One Big Beautiful Bill Act sunsets ever arrive. Wealth advisers increasingly advocate incremental gifting as the only reliable hedge against later cognitive decline that might otherwise lock assets behind guardianship proceedings.

Yet the heavyweight maneuver is the dynasty trust. Twenty-four states now authorize versions; Florida’s variant, capped at 360 years since its 2000 statutory overhaul, remains a magnet for HNW families whose heirs disperse across tax jurisdictions. sftaxcounsel.com Advisers are “decanting” revocable living trusts into GST-exempt dynastic vehicles before patriarchs and matriarchs reach seventy-five—well ahead of potential guardianship triggers—and they are layering directed-trust committees that flex around AI-generated tax-loss harvesting while stipulating sunset reviews every twenty years to assimilate whatever novel asset classes (tokenized real estate, longevity equity swaps, on-chain royalty streams) may dominate capital markets in 2045. The HNW Trusted Advisor Forum is a clearinghouse for comparative state-situs tactics, automated future-valuation models, and cross-border trust protector frameworks, offering a crowd-sourced roadmap that updates far faster than any legacy CLE manual.

Complementing trust architecture is staged succession inside operating companies: time-boxed CEO roles, external advisory boards with mandatory rollover, shadow-executive rotations that allocate decision rights before equity control formally vests. Here the AI/robotics wildcard intrudes: advanced automation could compress corporate life cycles, meaning the role an heir waited thirty years to assume might evaporate under a machine-learning pivot, leaving title but no enterprise. Families that recognize the risk build capital-allocation committees that sever ownership from management early, freeing the next generation to redeploy wealth toward emergent opportunities rather than clinging to decaying moats.

Policy Levers—Promising or Perilous

On Capitol Hill, retirement-committee drafts circulate under the informal banner of “SECURE 3.0,” flirting with raising the RMD age yet again—perhaps to seventy-six by 2030—while also widening 529-to-Roth rollover caps and offering payroll credits to firms that implement phased retirement tracks for senior employees. Proponents argue it will decongest upper-level positions by making part-time glide paths financially viable; critics counter that every upward tweak of the RMD age encourages wealth hoarding and postpones leadership turnover. In parallel, think-tank white papers weigh a Family-Enterprise Exclusion that would shelter closely-held business stock from unrealized-gain taxation at death, but only if majority voting control transitions before the decedent hits eighty—a bureaucratic nudge toward earlier hand-off but one that risks loophole abuse.

Internationally, the OECD urges tax credits for 55- to 70-year-olds who switch employers rather than stay put, reasoning that mobility, not retirement, is what frees junior headcount and disseminates knowledge. Critics doubt its efficacy in a labor market increasingly dominated by AI-assisted micro-firms where code, not humans, encodes institutional memory and therefore does not circulate when employees move.

The Singularity’s Shadow—and Why Every Projection Could Still Be Wrong

All of the foregoing trends—the widening inheritance gap, the leadership logjam, the housing choke point—are grounded in empirical curves we can plot out to 2055 with some confidence; yet every curve sits atop technological strata we can barely map. Large-language-model copilots already draft trust amendments in seconds; GPT-9-or-whatever will perform real-time stress tests against a family’s entire asset ledger, recommending gift timing optimized to moment-by-moment regulatory arbitrage. Robotics platforms are poised to lower elder-care costs so dramatically that octogenarians might maintain independent living with negligible family subsidy, delaying the day when liquidity must be marshalled for assisted-living fees. And if AI-enhanced longevity therapy jumps from mice to humans in the next decade—as early CRISPR base-editing results hint—then the ownership bottleneck tightens further: the ninety-eight-year-old settlor of 2045 may not be contemplating mortality at all but rather funding her second career.

In short: the only certainty is that technological acceleration almost certainly magnifies the existing delays; nothing on the near-term horizon shortens them. That reality demands strategic humility and structural flexibility—qualities traditional estate statutes and lifetime-employment models conspicuously lack.

Questions for You

How long could your family’s capital remain frozen if the senior generation lives to one hundred—and are your own plans geared toward stewardship rather than windfall?

What’s your scenario if any inheritance you expect is still decades away? Will you treat it as contingency—not strategy—and pursue opportunity as though it may never arrive?

Have you already encountered promotion bottlenecks or leadership stalls traceable to vertical longevity inside your firm, university, or nonprofit? How did you respond?

Join the discussion thread on The Long Tomorrow; share real-world timelines, friction points, and work-arounds; and watch The HNW Trusted Advisor Forum for deeper dives on mechanics issues the professional world is taking to address these issues and more.

"Robotics platforms are poised to lower elder-care costs so dramatically..." This may be true and I certainly hope it is, but it would be good to have some supporting evidence. Robotics has been making progress but is greatly lagging the rate of improvement in AI -- no doubt reflecting Moravec's Paradox. Robots for elder care could be an enormous growth area if engineers can get there. I would also love to see many robotic systems in space, building habitats and research facilities.